Ward F

A story about Marines wounded in battle fighting on the DMZ,

their struggles to recover from life changing injuries,

the Navy doctors, nurses and corpsmen who cared for them, and

the hostile “welcome home” they received from an ungrateful nation.

Official USMC Combat Art

Official USMC Combat Art

Patrick M. Blake

Dedication

To America’s Wounded Warriors who fought,

sacrificed and bled to protect our country.

To the Marines on Ward F who, in 1968, struggled

to recover from horrific, life changing injuries.

To the Navy doctors, nurses and corpsmen at the US

Naval Hospital in Pensacola who cared for the

Marines on Ward F and helped them heal their

broken bodies, minds, hearts and souls.

And to those Americans –

the politicians, news media, academics, and

everyday citizens who treated returning Vietnam

Veterans so disgracefully: redemption.

Forward

This is a story about the seriously wounded Marines and the Navy medical teams who worked tirelessly to heal their broken bodies and spirits at the US Naval Hospital in Pensacola, Florida, in 1968. It tells the story of the fight to recover from wounds, reconnect with family members, and the struggles to accept their injuries, the new realities of their lives, and the accompanying psychological and emotional trauma, all the while belittled and berated by their hostile and ungrateful fellow citizens.

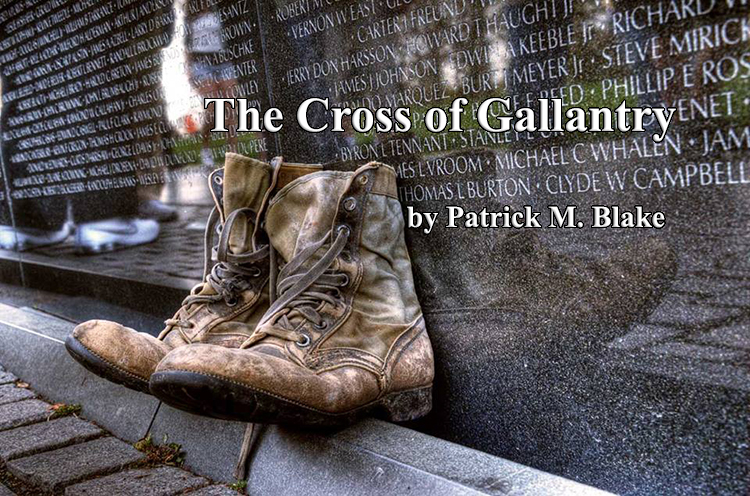

The number of Americans killed and wounded during the Vietnam War is staggering. The names of the 58,220 fallen heroes are engraved, honored and remembered on the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington DC. In addition to those killed in action, over 150,000 Americans were wounded and required hospitalization, most with horrific injuries. Gunshot wounds were the most common, followed by wounds from artillery, rocket, and mortar blasts that showered white-hot shrapnel ripping through the bodies of American warriors. There also were all manner and types of burns, stabs, punji stake punctures, and booby trap explosions that blew off limbs, blinded eyes, and disfigured faces. The number of wounded created an unprecedented flood of broken bodies that peaked in 1968, the same year when almost 17,000 American troops died in battle.

As the fighting escalated, the more severely wounded – those wounds that would not permit a return to duty in 120 days — had to be evacuated out of Vietnam. They were airlifted by the Air Force on cargo planes that had been jury-rigged to transport patients — stacks of hospital cots were suspended down both sides of the plane, running from one end of the aircraft to the other. The flights were from Vietnam to either military hospitals in Japan or military hospitals across the U.S. Unfortunately, an average of 45 days elapsed from the injury to arrival in a hospital bed in the U.S., and the survival rate for those evacuated was about 75 percent.

The military was ill prepared for the surge of Vietnam casualties — in the 1960’s, there were only about a dozen Naval hospitals, and another twenty Army hospitals available to care for the wounded. Military doctors, nurses, corpsmen and medics were overwhelmed with the flood, but they did an amazing job of repairing wounds and relieve the suffering. It is safe to say that wounded warriors will remember, and be eternally grateful for, the care they received from the military medical teams.

As the number of fully-loaded medivac flights to military hospitals in the U.S. grew, America’s citizens, the press, TV pundits and politicians were turning against the war. Protesters loudly clamored for the Government to pull out of Vietnam. And few, if any, showed concern for the casualties of the war. Most were indifferent to the wounded, ignorant of their sacrifice, hostile to the war, and disrespectful of anyone in a military uniform. The rejection and hostile treatment the wounded received from their fellow countrymen – the same ones they fought for — was in some ways more painful than the bullets, blasts, burns, shrapnel and lost limbs.

This is a chronicle of a year – 1968 – in the lives of wounded Marines on Ward F.

Chapter I – Grace

The Vietnam Women’s Memorial is adjacent to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall, Washington, D.C.

Cape Cod – Summer 2017

On a sunny, breezy Thursday afternoon in mid-June, Frank drove to the local grocery store to pick up essentials for the weekend. He knew it was better to shop on Thursdays before the new wave of tourists arrived, and most of the current visitors were busy packing their families for Friday’s drive home. The parking lot at Roche Brothers grocery was still crowded, but Frank found a space in front of the store.

The Cape is a beautiful place to live. During the summer months, the year-round population of over 200,000 residents easily doubles each week when out-of-town families rent homes and cottages. Locals stand in line with vacationers and wait to get a table at their favorite restaurants. Parking lots at stores and malls are packed, and finding a place to spread out your towel on white sandy town beaches is a challenge. Traffic jams in both directions at the Bourne and Sagamore bridges on Fridays and Sundays are legend, and it is common to wait hours to cross the bridges during the summer months. Most year-round residents are used to the crush and don’t mind sharing a little bit of heaven with their summer visitors.

Frank and Sandy O’Brian had moved to Falmouth in 2001 when they returned from Europe where Frank had worked on consulting engagements in Oxford England and Munich Germany. After a year in England and another six months in Germany, they were very happy to return home. The O’Brian’s were in their 60s when they found a home on Cape Cod, and Frank set up his home office for his software and consulting business. Frank continued to drive the business and traveled when necessary, while Sandy stayed busy with her passion – genealogy research on her English family roots.

The employees at Roche knew and liked Frank, an easy-to-spot year-round customer. Frank always wore his faded red Marine Corps cap, and he long ago had encouraged the staff to call him “Sarge.” He never spoke about his time in the Corps, so the only thing they knew was that he had been a Sergeant in the Marine Corps.

Frank took a number and stood in line at the deli counter waiting to order cold cuts for the weekend. As he waited in line, a short, grey-haired lady next to him said, “Hello Marine.”

She had bright blue eyes that stared straight up at Frank. “Hi, yes, I was in a lot of years ago. ‘64 to ‘75. Were you in the military?”

“Navy,” she said with a smile and nod, “I was in the Nurse Corps from 1966 through 1971.”

“Really,” Frank said. He paused. He took a closer look at the lady standing next to him, then asked, “Where were you stationed?”

“I finished nursing school at the University of South Carolina,” she said with a slight southern drawl, “and went to the Naval Hospital in San Diego for training.”

Her voice somehow sounded familiar to him, and seemed strained when she said, “in June 1967, I received orders to the hospital ship, the USS Repose, off the coast of Vietnam.”

Frank took a deep breath as memories began to flood back. “I was medevacked to the Repose just before T?t, 1968. I was too slow and forgot to duck.”

Making light of his war wounds was a habit. He never wanted to sound like he was whining.

“Multiple gunshot wounds,” he said in almost a whisper.

“Grace Beal,” the nurse said, extending her hand while staring straight into Frank’s eyes. They shook hands, and he could feel the strength, warmth and tenderness in her gentle grip that were very familiar to him from so many years ago.

“Number 24. Sarge, I think you’re next,” Sue announced from behind the counter. Frank shook his head and Sue went to the next customer. “Number 25?”

“Our paths may have crossed on the Repose in January 1968,” Frank said.

“Could have. I was assigned to the ER most of the time,” Grace said. Frank continued to hold her hand, and he could feel his chest heave. He remembered that day – January 19, 1968 – in Vietnam when he arrived on the Repose –

The sound of the CH-46 rotor blades pounded overhead as teams of Navy corpsmen filed up the back ramp of the chopper to unload the wounded Marines on stretchers. They jogged across the flight deck on the stern of the Repose, with Frank bouncing around on the stretcher, heading directly to the emergency room. Frank looked up and saw the captain of the ship, standing at the rail of the aft deck that overlooked the open hatch to the ER. The captain, standing at attention, saluted Frank and the other wounded being carried in for treatment.

There were several treatment tables with bright surgical lights overhead, each with a team of doctors and nurses waiting for the arriving patients. “Where you hit son?” a masked Navy doctor asked Frank as soon as he was placed down on the treatment table.

“Right shoulder, left foot, AK-47 rounds,” Frank mumbled in a whisper. The pain was excruciating.

With very large surgical scissors, the ER nurses and corpsman quickly, efficiently, and gently, cut off Frank’s boots, jungle utilities, flak jacket and shirt. He lay naked on the table and someone spread his legs apart while a nurse with a large syringe in her hand wiped the inside of his thigh with a cold, wet swab.

“Ahhh. Hold it! Wait a minute! What the fuck are you doing down there?” Frank half yelled and started to sit up to see what was going on.

“We need to take some arterial blood for the lab,” the masked doctor explained as he pulled Frank back down on the table. The nurse ignored him, inserted the needle, and drew his blood.

“I’m with the Red Cross,” announced a masked brunette standing behind the medical team. “We need to notify your next of kin about your injuries. What’s your name, rank, service number and home of record?”

Frank’s mother had a serious heart condition and he didn’t want her to be told by strangers that he had been wounded. The shock could kill her. “Don’t tell my mother,” Frank said through gritted teeth, as the doctors examined, probed and cleaned the gapping bullet holes in his right shoulder and left foot.

“Both rounds went through and through,” a doctor told the nurse who was taking notes.

“Francis Mahoney O’Brian,” he said to the Red Cross worker. “Private, 2054299, Alexandria, Louisiana.”

The doctors put a bandage on the entry wound in the front of his shoulder and then rolled him over to bandage the exit wound. The exit wound was much larger and the doctor was trying to stop the oozing blood. His shoulder hurt like hell, and his foot felt like someone dropped a brick on it.

“Don’t tell my mother,” he said. “Please don’t tell my mother – tell my brothers. They live in Baton Rouge,” he said. Frank recalled that his older brothers, Sean and Kevin, lived in a student apartment complex on Airline Highway. Both were attending LSU. The Red Cross would have to find their address.

“Get him to X-ray and then take him to surgery,” the Doctor said.

“Damn. It feels like they are on fire,” Frank said to no one in particular.

A pretty, dark haired, blue-eyed nurse had held Frank’s hand throughout the exam, “you’ll be OK Marine” she said in a gentle and reassuring voice. Frank closed his eyes and fought back the tears. She squeezed his hand and whispered, “it’s OK. You’re going to be OK.”

Frank became aware that “Sarge” and “Number 24” was being called out again. He looked down and saw that he was still holding Grace’s hand. Frank gently released it, then reached out and gave Grace a warm hug. The nearby shoppers in Roche looked on and tried not to stare.

They stood for a moment, holding each other and Frank whispered, “Thank you. You know, we Marines loved you Navy nurses.”

“And we loved you right back,” Grace whispered. “Welcome home.”